De-colonial Design and Indigenous Methodology with Tsēma & Jonathan Igharas

Interdisciplinary Artist & Industrial Designer

Vancouver, BC & Brooklyn, New York

February 2017

Even with the year-long planning and preparations from Vancouver, there was still so much left to be done upon arrival in Batan. Tsēma and Jonathan Igharas were to be the first artists in residence. Having Elmo’s House open only a week before, the Residency was harried to receive its very first guests.

Arrangements were made to meet at the back parking lot of Gaisano Mall in Kalibo, an hour drive away from the house. The logistics were planned precariously over text and lengthy back-and-forths ensued. The anticipation was palpable. To maximize the time in town, multiple house errands were made, all the while watching the time to ensure the scheduled meeting is executed without delay. With groceries and supplies in tow, apprehensions dissolved to excitement as both artists came into view. With hands on hips, Tsēma was facing the wall and contemplating a hand painted message in Tagalog, “you can’t pee here”. Jonathan sat on a bumper block with camper packs and rolling suitcases poised around him. It was a hot afternoon and both seem blissfully resigned to the sticky air.

Tsēma and Jonathan Igharas are on the cusp of forging a collaborative partnership though their new company Make Shift. It’s a creative agency rooted in De-colonial design and Indigenous methodology. Tsēma is an interdisciplinary artist and member of the Tahltan First Nation. Her education and emerging art career is devoted to exploring issues around contemporary First Nations in Canada. Her artistic work grapples with the body, her body, as it has witnessed both material and metaphysical landscapes changing and continually impacted, shaken and consumed by corporate resource extraction. Jonathan, on the other hand, is a multidisciplinary designer and maker whose background is in Industrial design. His projects, made distinct by the balance between utility and refinement, are socially active and engaged. In short, these two have found convergence in Make Shift. It is the perfect way to round off their collaboration in art and life. This new venture seems like a natural trajectory that encapsulates their ancestry and future.

Jonathan, you produced some key pieces to be used in the residency. How did the environment affect your work?

The environment at Elmo’s House gave me the freedom and space to focus on my projects. It also offered clear design constraints due to Batan’s rural location and limited access to resources, tools and materials. This proved to be challenging at first. Being accustomed to working in New York City, I had access to anything and everything at anytime. In the end, it simplified my process and allowed me to produce a significant amount of ideas and work within a very short period of time.

Tell us about the building process.

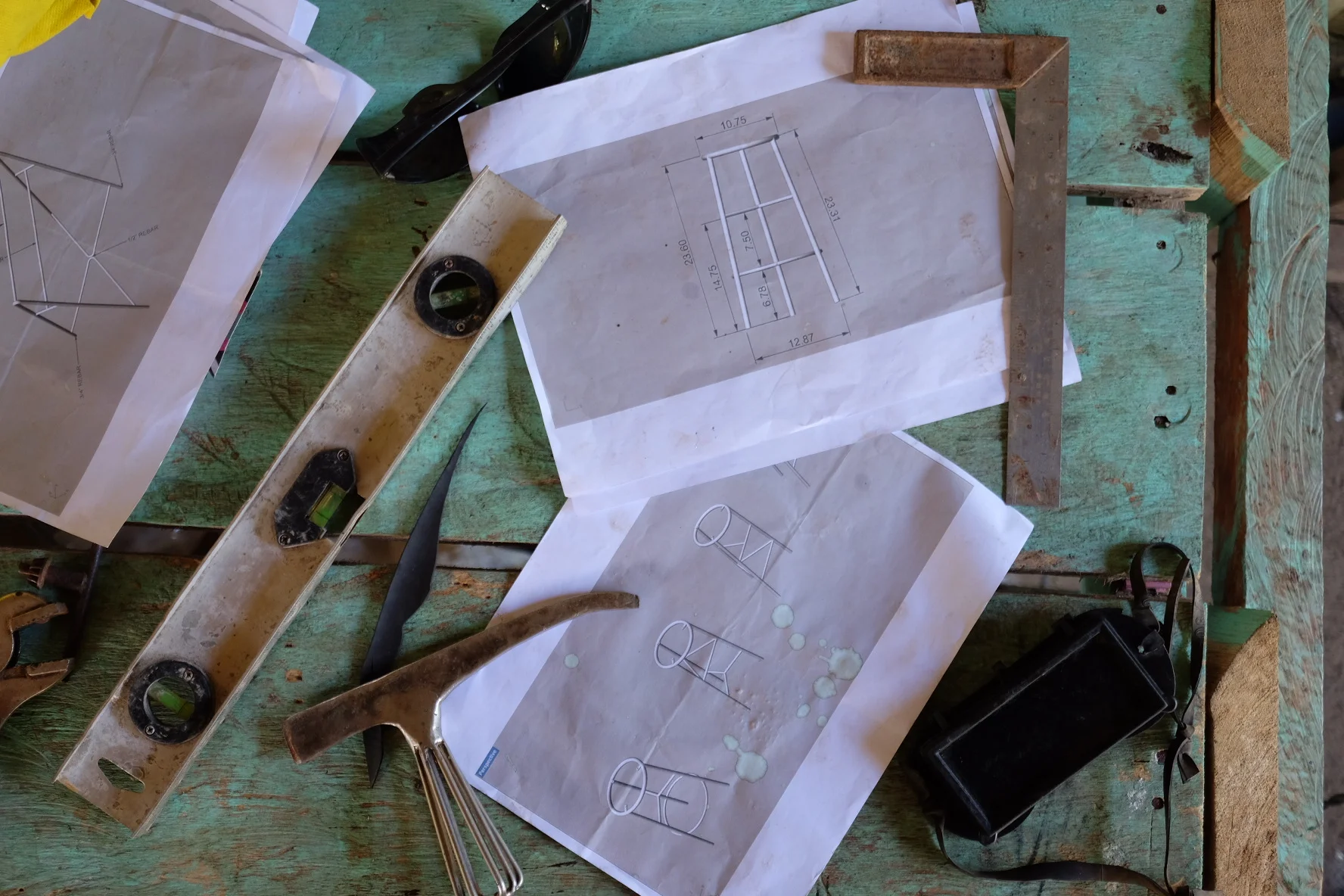

My building process in the Philippines starts off with taking notes and photos of everyday objects that I consider to be uniquely Filipino. It could be about the combination of materials used or the way it’s unconventionally fabricated together. I’m inspired by how each can form something that’s different from what I'm typically used to. I truly believe there is genius in the simplicity and practicality of Filipino Design. From these observations, I begin by making sketches and scale models to better understand how the materials physically come together. I then move onto the computer and use 3D software to help model the idea forward. I create prototypes that allow me to create many design iterations. These help me decide on proportion, size and composition. The chosen models are turned into 2D drawings that include dimensions, materials and fabrication details for the maker to follow.

Tell us about the work station you designed and built for Elmo’s House.

The custom rebar and solid wood workstation I designed for Elmo’s House was the product of observing local building materials and construction methods in the Philippines. Combined with the Residency’s need for a simple yet functional work surface, the long table and stools became a key project that will be used by future Artists at the Residence. I used solid steel rebar rather than hollow steel tubing because it’s readily available and affordable. It’s easy to bend by hand and a familiar material local fabricators would be receptive to work with. It was reflective of being in a rural area like Batan. Having limited access to special tools, materials and resources, as well as having a limited amount of time, it informed many of my design decisions. I was able to source a metal worker and a wood shop with the help of Tsēma and the Residency. The project was completed all in one week! It was very satisfying to work on. Not only because of how fast the design and build process was, but because we were also able to personally connect and work with local builders and craftsmen.

It was very satisfying to work on. Not only because of how fast the design and build process was, but because we were also able to personally connect and work with local builders and craftsmen

Meeting Eliazar

Early in Tsēma and Jonathan’s residency, while driving along Batan Road, Tsēma spotted a hand painted makeshift sign on corrugated metal. It was advertising for Eliazar’s services. The road was a winding twolane highway that cuts through most of Batans’ twenty barangays. It should have been an easy marker to miss, yet it stood out among the lush greenery that lined either side of the road.

Eliazar Oliveros is one of a few iron workers in town. Littered with bespoke tools and equipment, his workshop sprawled under a bowing tarp. Tsēma and Jonathan inquired to see what type of craft he offered. With careful movements, Eliazar returned from his shed carrying a canvas book. He held it preciously, carefully opening each page. It was an old design catalogue of elaborate and diverse iron works. Illustrated gates, fences and window frames filled the pages in black and white. They ranged from the very ornate to the simplest forms. It served as Eleazar’s portfolio. He can do anything that’s in the book and more, he expressed. He was known around town for his spiral stair cases, so a workstation out of rebar was a reasonable task.

The table was completed in record time. Baku solid mango wood was used for the tops. Sourced from a custom furniture and woodworking shop in Altavas known for crafting extravagant china cabinets, beds and cupboards. Tsēma and Jonathan generously donated the finished table and stools. It currently sits on the studio floor overlooking the town square.

Giving local makers the designs was a kind of letting go

Tsēma, you have an amazing understanding of material, how did Elmo’s House and it’s surroundings add to this?

From my brief time in the Philippines, I have observed an industrious creativity that comes out in everyday design and assemblages. This is the root inspiration for both Jonathan’s work station and my feeders project.

For the work station, we proposed something that bettered the community. Not only did it immediately affect the residency while working with local artisans for it to be realized, but it allowed us to build relationships. Rebar was everywhere and it became the bridge that enabled the project. It is workable and inexpensive. If Eliazar wanted to replicate this table, he would be able to. It was a De-colonial design experiment. Giving local makers the designs was a kind of letting go. A letting go of the exclusivity that design and future commerce brings. It empowered the makers!

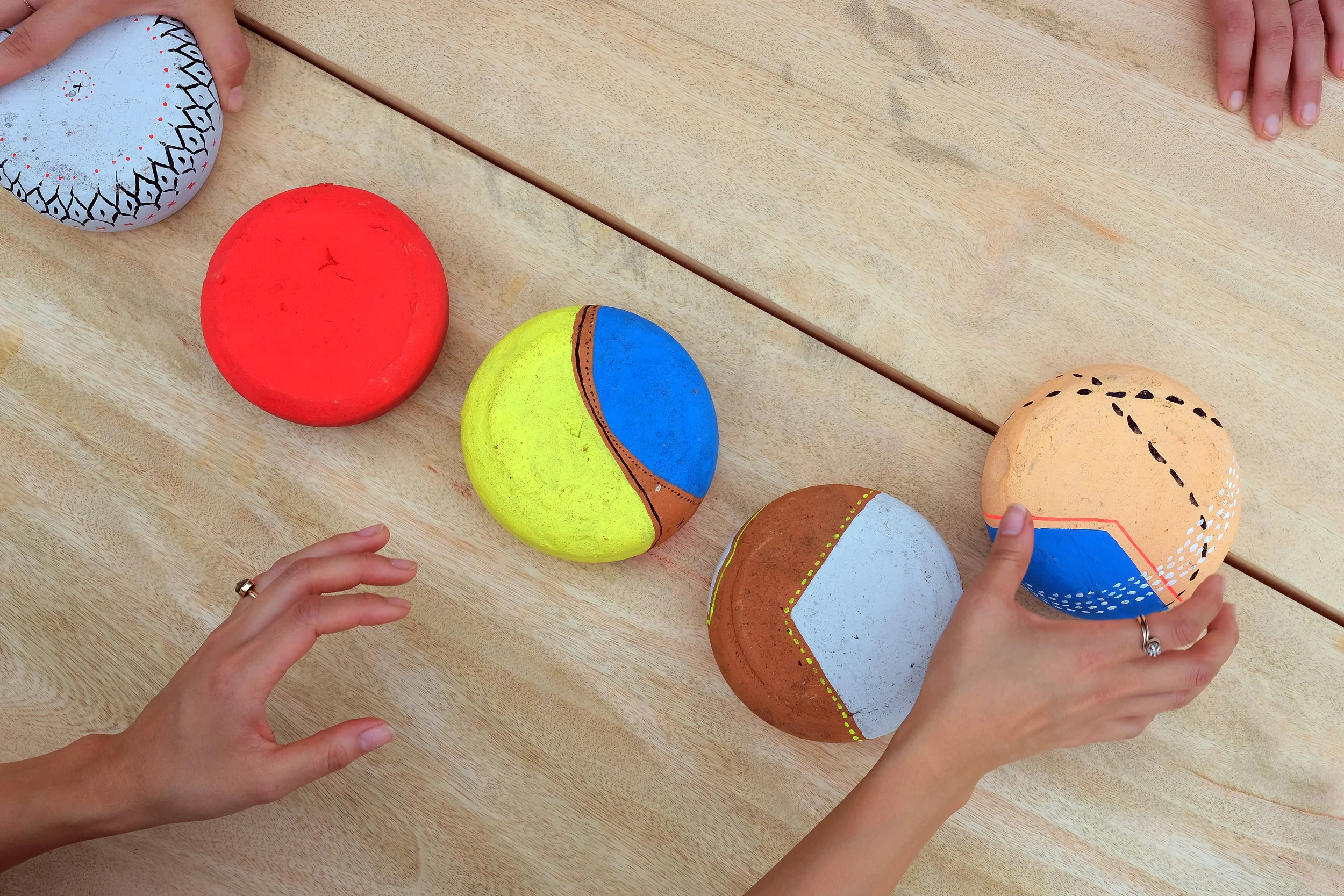

Tony, Jonathan’s cousin from Kalibo, drove us to Lezo one day. There is a pottery making village and market situated there. The clay they use is gathered from the local river bed and mixed with sand for stability. It starts out yellow in colour and fires a terracotta red. It has a beautiful clay body, but we struggled to find something that suited our taste while being small enough to bring home with us. But it was perfect for my chicken feeders project. As an object, the bowls were already the perfect shape and material to feed chickens with. I decided to explore and play with designs that incorporate into its shape with the Filipino cock fighting culture as inspiration.

Year of the Rooster

The 6000 year old practice of Cock Fighting in The Philippines is as fervent as ever. Despite having a history of state and religion fighting against it, it has endured with the masses. Tsēma and Jonathan witnessed first hand how a cock fight can engulf a community into frenzied excitement. Bank rolled by big named companies, it is massive business. Droves of carnage enthusiasts, mostly men, pack octagonal arenas to cheer and bet on their favourite game cocks. Before the climax of these events, the pedigrees are treated to months of training and conditioning. High quality feed is served to strengthen fighters in preparation for game day. It was an inspiring phenomenon that informed Tsēma’s performance piece, Year of the Rooster. Tsēma brought a set of unfired red clay bowls from Lezo. Each were hand painted with colours and patterns that drew from both Tahltan and Filipino designs. She went around offering her bowls to proud owners. Encouraging them to feed their warriors from the lavish colours and patterns. A gesture that emulate the banquets we offer to our athletes and gladiators.

Year of the Rooster is an investigation into a culture that knows how to revere. Fighting cocks are allotted time, space and vast resources in preparation for the fight. But rather from an economical perspective, Tsēma’s performance approaches it as a study in love, specifically Pinoy love. Food is an unavoidable gesture of affection in the Philippines. It trumps any economic climate and equals the importance of religion in every Filipino. Food is offered freely and abundantly because it is vital, not to survive, but it gives reverence to who the Filipinos offer it to.

Since both your work relies heavily on raw materials, how was it looking for resources and connections in a small town?

Serendipitous. A rule that we made was to source or use something we already had (repurpose). We have been on the lookout for project inspiration and materials during our time at Elmo’s House a few weeks prior. Most of the items we brought with a loose idea of the projects in mind. Aside from my paint and the clay pots, everything was sourced from the Batan area.

What’s your favorite part of Batan?

Tsēma: I loved the character of Batan. The people are so nice and extremely curious. We kept getting the feeling that people were hanging out in the square to see what we, the foreigners, would do next. We were probably wrong. We were, at one time, suspicious of a few individuals in hooded sweatshirts repeatedly appearing in front of the Residence. We learned later on that they were just doing running exercise laps around the town square. Ha!

Jonathan: My favorite part of the Batan is its location in the province of Aklan. I’m biased because this is the same province where my father’s family is from. It’s also just an hour away from where I consider my second home to be. Another reason is its proximity to the ocean. Batan’s surrounded by water. It’s so lush and green here.

What made you come to Elmo’s house?

Tsēma: We had planned to travel and do work in the Philippines for a few months. Since the Residency is very close to Jonathan’s family home in Kalibo, we thought how perfect it would be for us to incorporate this opportunity. Also, after a few solo art and design residencies in previous years, Jonathan and I have been wanting to do one together.

Jonathan: I wanted to be part of a hub for creative thinking and critical discourse in the province of Aklan. The purpose of Elmo’s House is meaningful and I fully support anyone that helps to promote the arts and bring international exposure to the Philippines.

What was your regular routine while at the Residency?

Tsēma

Coffee first. I started with those nasty three in one packets that I thought was the only way until I was introduced to Nestle instant coffee with vanilla milk. It was pretty good and it did the trick.

A few days into the Residency, I’d fix myself up some of my homemade Kalibo Market Mix with some local bananas. It turned out better than I thought!

I would then take care of my emails, either at the dining table on the ground floor, or at our workstation upstairs.

Later in the day, I would try and work for part of the day. On some days I’d continue working on flash card illustrations for Tāhłtān language learning. I would usually reward myself with painting the chicken feeders afterwards. The feeders, at first, were only surface experiments, observations and responses to my surroundings. As the process progressed, it became a playful nod to the Filipinos’ love for their roosters and to what I’d like to call “chicken performance art”.

Partway through the day, we would go exploring and source more materials for the work station project. At some days, we would gallivant around the Batan area. Most of the time, we’d do both.

Jonathan

Wake up around 8AM and continue to lay in bed for another half hour or so listening to the random, faint sounds coming from outside our bedroom window (dogs barking, kids playing, motorcycles driving by, sweeping, etc.) while thinking about tasks for the day and new ideas for projects.

Eat breakfast. A banana or two, bread with preserves, Tsēma's Kalibo Market Mix with almond milk (a rare item to find). Or, a simple Filipino style breakfast: white rice with an over-easy egg and some protein.

After breakfast, I’d walk upstairs to the shared open studio floor. I’d check emails, social media accounts and transition into work developing project ideas using wire models and 3D software.

Take a break to stretch, do a few sets of pushups and have a small snack. And then continue to work until Marie-vic calls us down for lunch.

After lunch, I worked to prepare fabrication drawings for our vendors to begin production, and then usually as a group we would run errands around town. We’d pick up supplies, look for material inspiration and source vendors to work with. Afterwards, if it wasn’t too late in the day, we would explore the surrounding areas, especially the beaches, since Batan is surrounded by water and near the ocean.

We try head back to Elmo’s House before sunset to relax and help in dinner preparations for dinner.

After dinner, for a couple days we had a streak of playing card games while drinking homemade sangria or Red Horse beers. We’d chill, let loose and get to know each other a little more. This would continue until we realize that we are all lightweights and we’d usually go to bed before midnight!

We have a common passion that ties us together for the kind of work we want to be involved with in life.

Do you enjoy working together?

Tsēma: Yes! We have had our challenges, but we continue to get into an organic and productive groove. Unfortunately, we also influence each other in our procrastination. We are working on that.

Jonathan: I agree with Tsēma. We have our moments of difficulties working with each other just as any working partnership has. But we truly do compliment each others skill sets. We have a common passion that ties us together for the kind of work we want to be involved with in life. At the end of the day, we are able to take a step back from our small battles. It creates a resolve. We learn from the challenges that we come across together when we collaborate.

How did the two of you meet?

We both worked at the "tool crib" at Emily Carr University of Art & Design in Vancouver where we both went to school. The "tool crib" is basically a library for tools that students and faculty could come to and rent out from. It was the best job you could get as a student because you can do your home work during your shifts. Anyways, Jonathan and I were scheduled back-to-back, me in the afternoon and him in the evening. He liked my bike. And it started from there.

How has Elmo’s house enriched your trip?

Elmo’s House gave us the freedom to create together as a couple. We were able to have productive dialogues about our practices, and shed some light on the politics that surround our identities and work. Elmo’s House was amazing timing for us as artists and especially now as we build Make Shift. We have been discussing Decolonial design and the future of our practices since Jonathan quit his job. It was the time to act. Elmo’s residency was the spark to create that space.

What is your company Make Shift, all about?

Make Shift is a nomadic creative agency that specializes in critical art and inclusive design. We employ Indigenous methodologies and focus on cultural and community-centric design. We make use of renewable materials and social design principles. We recognize material significations coming from history, popular culture, and our ancestors who have associated meaning and value to materials for their artistic and utilitarian potential. It is our goal as partners in business and in life to create a professional practice that bridges our respective ancestries: Tāhłtān-Canadian and Filipino-American. We hope to utilize our educational backgrounds and interests to allow us to work globally and across various cultures.

You both have been traveling for a while now. Can you share with us the places you have been to in the last 6 months?

Since our Tāhlipino Union, Jonathan travelled from Vancouver back to NYC to finish up his design contract. I traveled to the Banff Centre for Creative Arts and completed a month long Indigenous themed residency. We reunited back in Smithers, BC at my family's home for Christmas and then traveled to Tokyo, Japan for New Years Eve. We spent two weeks there and most of our honeymoon fund. In mid-January, we arrived in the Philippines. We started the trip in Siargao where we surfed in-between the heavy rain storms and floods. We acquired a motorbike and explored beaches that lined the island. We headed to Boracay afterwards just before travelling to Batan for our two week Residency at Elmo’s House. Since Batan, we have traveled to Manila, attended a startup business camp for social entrepreneurs in the Bulucan Province, and then continued north to Baguio, Sagada, Banaue, and Batad to explore the Cordillera Mountains. We wanted to learn a bit more about the Indigenous Igorot culture of the Philippines. It has been an epic extended honeymoon, research and adventure trip so far and we hope to continue living and working nomadically for the next year when we return back to Canada and the US.

What do you both see yourselves doing in 5 years?

Living and working nomadically in a customized camper van with our future dog. We’ll be making art, designing products and continuing to fabricate custom bikes and trikes. We will further our research in De-colonial design while planning our next travel adventure to wherever our business takes us.

Tsēma and Jonathan’s participation was the beginning to a dream being realized. They were the much needed jump-start to Elmo’s House. Their level of involvement and passion not only brought on such a positive impact, but seeing Batan and Elmo’s House through their eyes was simply joyous.

Tsēma Igharas

esln.ca

teaandbannock.com

@tsema_rockmother

Jonathan Igharas

jsigharas.com

@jsigharas

Tahlipino

tahlipino.tumblr.com

@tahlipino